Two Middle-Aged Women on Walkabout

Caroline and I first met in 1986. I had puffed my way up Park Street in Bristol

and walked into a slimming centre where Caroline was then working. We immediately clicked, ignored the slimming,

and went to lunch together. She lives on

Gozo now, and my footsteps have once again brought me to Glastonbury from the

other side of Earth. During a

conversation at the end of our first connection Caroline confided to me,

prompted by my still Australian accent, that she had wanted to come to

Australia since she was ten years old.

A decade had passed since that

conversation and I was again in Australia.

Emails were new magic, so when Caroline emailed me with the news that

she was coming to visit me in October, 2001, just a few months hence, I was thrilled. It was in celebration of her 60th

birthday. She wanted to visit sacred

sites, to meet an Aboriginal Elder. She

was not coming, she emphasized, to visit white

Australia. I could organize her first wish, could certainly steer clear of the

last, but could only send out songlines for the second. However with a longing

as great as Caroline’s I felt confident we would be guided to exactly where we

needed to be.

I had planned for us to go to Uluru but

with the collapse of our major internal airline, Ansett, just days before

Caroline’s arrival we couldn’t get there.

I was tempted to wonder (with a smile in the mind’s eye) if the entire

world bent itself for 2 women on a spirit journey because, unknown to either of

us then, our destiny was plainly written in the stars.

Caroline

arrived at the tiny tropical airport of Townsville wearing dark blue woollen

trousers and a huge pink polo neck angora jumper in the hottest October for

years. She and her luggage were among

the first off the little plane which brought her down from the international

airport at Cairns, and we bundled everything into my old Alfasud. She marvelled at the fact that she simply got

off the plane, walked across the tarmac, and found me just inside the

door. And we walked together out of the

door on the opposite side of the airport building to my car. This is worthy of note, for Townsville is the

most pleasant airport in Australia. Alas

both it and the centuries old World Heritage bird and wildlife sanctuary known

as The Common, adjacent to the airport, have their days numbered. The airport has been sold privately and the

new owners have grandiose plans for its future development. Those plans won’t

include bird sanctuaries. It may not be

long before landing in Townsville will be just another homogenous airport

experience.

Caroline

was melting like a raspberry sundae but I stopped along the airport drive to

show her a Bowerbird nest in the bush beside the road. Its arching bowers were lined with the bits

of blue anythings that so fascinate this bird; plastic, paper, bottles, pieces

of glass; even an old blue hairbrush.

Mother Bowerbird uses this bower every nesting season, adding to the

blue decor.

She

responded with delight at the scenic route as I drove along the newly created

Strand with its palms and sea and art work and play areas and shaded sails; the

colourful, chattering Lorikeets and elegant high stepping Sacred Ibis enchanted

her. Magnetic Island was a hand length

beyond the stretch of sea. For first

impressions, this was pretty impressive.

Southerners sneer at Townsville, never having visited, but as

Australia’s best kept secret that’s fine and dandy, and long may it remain so.

Once home Caroline peeled off her

woolly winter persona, showered, put on a cool turquoise sarong I had laid out

on her bed, ate some fruit and yoghurt, and had a comforting cup of good

English tea. I wouldn’t let her sleep;

jetlag is best dealt with by tuning in to local time, I can be cruel! Distraction is the key and we went straight

into town for some suitable tropical retail therapy.

She bought

three delicious dresses. Two of which designs were to flavour and favour an

Aboriginal spirit journey, plus a filmy layered turquoise and sunshine yellow

French number which naturally needed shoes to match. I owned variations on the

same themes. Off then to Papoucci to buy

the most enchanting pair of sunshine yellow sandals with clusters of tiny

yellow flowers across the toes. And then

a hat. Back we went to the gals of

Townsville Hatters for a wickedly wonderful hat which was to become another

part talisman for our pilgrimage. When

one is searching for the Divine my maxim for any pilgrimage is that one must

dress divinely.

For the first few days we did low-key

tourist things. Caroline took the

obligatory trip out to the Great Barrier Reef, did her first scuba dive, and,

water baby that she is, became so enchanted with the wonders under water that

the pleasure boat crew had to haul her in mermaid fashion. Magnetic Island proved itself as magic as

always. Wearing our grand hats to shade

us against the searing sun we climbed the high Fort Walk and found koala bears,

somniculous in their eucalyptus. Only mad dogs and

English women go out in the midday sun and when we reached the summit our legs

could barely support us, or our hats. A gracious brick layer, going home for

lunch in the heat of the day, warmed to two elegantly hatted figures tottering

down the hills in the noon day heat, took pity on us, and offered us a lift to

where ever we wanted to go. Which by

then was Magnetic Mango, en plein air, to sit under the huge mango

trees and eat gourmet food and drink delicious mango smoothies. As we recovered our sang-froid a large camera lens drew our attention. The man behind the camera asked if he could

take our photo – he and his wife were on holiday from New Zealand. They had come to see the sights, and

according to him, our hats were a real sight…

Days drifted by in this idle manner

while we discussed and re-discussed our route north. Everyone said we were mad

to try and pack in what we intended us to see.

Of course they were right; I knew that.

But Caroline, from Cornwall in the West of England, had little

comprehension of distances. The closest

town north to Townsville is 110 kilometres, and we were planning twenty times

that distance. A couple more days of hearing this from everyone she met and

Caroline extended her stay, altered her flight ticket, prepared herself for

flexible possibilities.

There is a special story that Carl Jung

used to tell of a shaman, a rainmaker, who was called by the people of a

drought stricken village to come and bring rain to save their harvest, their

livelihood, their life. He duly arrived,

and requested a hut and solitude for four days.

Food was to be left outside his door for him to take as he needed. On the fifth day he would begin his

work. On the fifth day the shaman made

preparation to come out of his room to begin his rituals and ceremonies for

rainmaking. Yet before he could do anything the heavens opened.

The moral of the story, as we know, is

that when one is in right accord on the inside powerful forces are drawn

together on the outside to stimulate the processes and needs of life

itself.

The rainmaker, after his long journey, was not settled enough to communicate the needs of the villagers to the elemental realms, but because rainmaking was his destiny, his soul’s work, once he was settled in himself, his own songlines of destiny were cleansed and calm and the greater forces naturally came into harmony to respond. In human experience Jung named this synchronicity. My spiritual teachers call it by many different names, but I particularly like Mrs. Tweedie’s “eavesdropping on the Heart of hearts”, listening, in other words, to the Hint.

On our first Saturday morning together

I took Caroline to Mass at the House of Prayer.

The priest that day was an especially sensitive man and his homily of

the ghastliness of the Australian government’s attitude to the refugees dying

on a ship off our shores (they were refused asylum) made her weep. She had never

in her life been to a Catholic Mass, or imagined such a priest. We all sat in comfortable chairs in a circle,

and Dave, the priest, sat in the circle with us. He wore his usual weekend T-shirt and

shorts. Most of us, including Dave, kick

our sandals off at the door. It is

communion at a deep level, where we are indeed all part of the One. Caroline saw Dave bathed in light, a lilac

light, as he spoke, and the light surrounded another special man present, an

ornithologist whose support of the House is a gift to us all. That afternoon we visited World Vision, known

as Oxfam in England, where Caroline found an olivewood carving from Palestine

of Our Lady and had to buy it. The

Goddess had touched her.

We decided to leave for our pilgrimage

on Tuesday at dawn. We chose to hire a

car because my old Alfasud has no air-conditioning and the October days were

steaming up considerably. Should we

encounter tropical rain it would be like driving in a sauna with the windows

closed in my car, so air-conditioning made common sense. To make the trip to Split Rock, to the sacred

Rock Art of the Quinkan Country near Laura, up in the Gulf, we would need an

off road four wheel drive vehicle later on as well.

The rental car company was kind enough

to let us take the car early on Monday afternoon as their office was not

opening until after we had planned to leave the following day. This meant we could load up the night before,

ready for the dawn departure. The next

morning, after tea and fruit, we left for Ingham, known affectionately as

Little Italy. The most beautiful terrain

of tropical North Queensland begins beyond Ingham. I make a habit of stopping in to see Tony,

from Sicily, at the Olive Tree for a cappuccino and Australia’s best

bruschetta, made with Tony’s home grown basil and garlic. Thus fortified I can do justice to the

unfolding panoramas of the drive ahead.

We took an Italian opportunity to load up with Italian cheeses and

imported olive oil and balsamic vinegar and artichoke heads and delicious

Italian breads and olives, as well as other tempting tidbits for the picnic I

had planned in the Licuala forest of Tam O’Shanter National Park near Mission

Beach. I sent out songlines for a

cassowary, a not too impossible request, as this is their habitual territory.

The day went well. Caroline agreed Tony’s bruschetta was

excellent; that the sight of the Hinchinbrook inlet was awesome; and that the

Cardwell National Park Habitat Centre the best she had seen. We drove on and into the National Park where

we set out our picnic under the licuala canopy and Caroline got goosebumps when

a cassowary came within coo-ee. It

stayed watching us a long time, bowing its horn-crowned head and its long blue

neck. These huge flightless birds stand

a metre and a half tall, five feet tall in oldspeak, and they fertilize the

ancient rainforests by travelling great distances and carrying and dropping

seed. The survival of this shy giant

bird is in serious question, larger pet dogs being responsible (and their

owners irresponsible) for killing as many as are killed by careless drivers as

the birds cross the bitumen roads that now divide their ancient forest

territory. Later we stood breathless for

long moments at the palm-fringed sweep of Mission Beach where it seemed the

world, for that single span of time, had bequeathed to us alone its share of

Paradise, its white sand, turquoise seas and tropical islands just a finger

touch away.

We skirted the coast road around Bingil

Bay to arrive at El Arish back on the highway north, and turned left at

Silkwood to climb the Tablelands to Paronella Park. Silkwood is known for its 3 saintly relics

from Italy, for this is the heart of sugarcane country where Italian immigrants

came and suffered greatly in the early years of settlement. From here on I drove, so that Caroline could

absorb the extraordinary panorama of green rolling hills, forested or pastured,

ringed with range on range of mountains in silhouetted shades of deepening

blues and mauves as we drove higher and higher.

We reached Paronella by 3 o’clock, in time for Mark, the owner, to

attach us to a guided tour of this magical place. Paronella was the vision of one José Paronella,

who arrived from Catalonia in 1913. It

has a sad history, and José eventually died of cancer brought on by a broken

heart after insensitive neighbours had refused to clear backlogs of fallen

timber banked up river, which in the great floods of 1946 created a colossal

tidal wave which swept down and devastated his life’s work. Yet his vision lives on in the astonishing

beauty of the parks and grand avenue of kauri trees he first planted, now a

towering 30 metres, and the lichen covered ruins of the castle he and his wife

laboured over for decades to build by hand. They dreamed of castles for their

children, they dreamed of grand staircases and chandelier’d ballrooms for their

community, a quixotic blend of old and new world on a miniature, but hugely impressive,

scale. Alas Australians were not ready

for such cultural transplants. José and

his wife mixed and processed every ounce of concrete themselves, their

handprints plainly visible in the ruined façade. The website of Paronella gives a glimpse into

this magical place. We left on closing time, to begin the still lengthy drive

to Atherton where we were to stay the first night with a friend who has an

orphanage for spectacled fruit bats. A

photo of her tiny orphans was the London Times Magazine photo of the week a few

weeks before Caroline’s arrival, and she wanted to see the orphanage for

herself.

Now, the road between Paronella Park

(the Catalonian vision), and Pteropus House (the bat orphanage), is through

many miles of high rolling grazing land, partly forested, with very little

evidence of human habitation. We had

seen virtually no traffic all day. Suddenly, on a high range with spectacular

views, two cars seemed to appear from nowhere to close in behind us. We turned

a bend and met with two cars coming in the opposite direction. Because of the two oncoming cars the

impatient ones behind could not overtake us.

And just as well, for there in the centre of the road was a tiny,

terrified, black kitten.

I braked, leapt out of the car, ran down the

middle of the road frantically flailing my arms to halt the other cars while I

let the kitten negotiate his getaway.

But the little soul turned, took one look at me, and ran full pelt to

leap into my flailing arms, which naturally closed about him. But now what?

I could hardly turn the kitten back onto the road, and there were no

houses until the next township, 20 kilometres away, he could not have wandered

so far. On close examination, back in the safety of the car, s/he (too small to

tell) had torn paws and split claws and had scuffed raw the skin and fur over

its eyes as if in a tumble. We

backtracked to the sugar mill, but no one wanted to know about a kitten. One man offered to take it to the animal

pound but neither Caroline nor I had the heart to end its life after such a big

adventure for such a small kitten. The man there told me that just yesterday he

had rounded up a batch of kittens to take to the pound as a sack filled with a

litter of kittens was hurled from a passing car. It was likely that this kitten

was one that got away and it was now curled up exhausted, and very dehydrated,

on Caroline’s neck. We continued on to

Pteropus House, still two hours away.

Having The Birl (we didn’t know if it

was a Boy or Girl so we settled on The Birl, rather better than Goy…)

completely altered our plans. Down on

the coast and inland at Split Rock the daytime temperature was so fierce we

could not leave anything in the car while we were sightseeing. We were already using the air-conditioning at

its highest as we drove. The immediate

challenge ahead of us was finding somewhere to stay with a kitten. Cruelty to

cats and kittens (and possums and kangaroos and wild horses and dingoes and

just about everything other than expensive dogs) is a sad reflection of the

less attractive side of life in Australia - something awry with their

connection to the Feminine, and to Mystery, I believe. Would we find a B &

B to welcome the three of us?

I was once taught by an Inuit shaman

(from north of Nome) with whom I was privileged to work that no spirit journey

can commence without a power animal, without a test by Mother Nature herself,

and without humility on the part of the seeker.

Now a power animal is not something we choose for ourselves, our mind is

too limited, too conditioned by prejudices of received opinions. We all want elks or mountain lions, kestrels

or eagles, when in fact if Spirit is telling us we need to be grounded a carrot

vision might be exactly what we are sent.

Caroline had stated emphatically that she had come to Australia for

black Australia, not white Australia, and she also knew that there was no such

thing as happenstance when one began a journey with sacred intent. This kitten was black, coal black, and its

arrival would alter all the best-laid plans of mice and men, as well as those

of two middle-aged women on walkabout. I

let Caroline determine the kitten’s fate, and in doing so, the direction of our

journey, because I left the decision to her as to whether a weak black kitten

was a power animal for two middle-aged women on walkabout. I can be heartless! At the first night’s destination we both knew

all was exactly as Planned.

We

arrived late to Pteropus House. Jenny,

the owner, was out collecting her nightly quota of orphan pteropi, spectacled

fruit bats. Claire who greeted us was a

guest resident and English. She and I both knew that Jenny would not want cats

on the premises – but it was so-o-o late and the kitten was so-o-o tiny, so-o-o

tired … and so Claire said, her English compassion coming to the fore, just

stay and rest.

We

fed The Birl who ate without break like the starved kitten s/he was. I

introduced the litter tray. No way! Yet s/he was obviously distressed and needed

to piddle. Brainwave – I brought in a

scoop of good earth and sprinkled it on top of litter perfumed to appeal to

humans and voila! The Birl jumped in,

scratched a wee hole and emptied a bladder so full we turned our heads away and

laughed, not wishing to embarrass one so well-mannered kitten. All sorted, we thankfully showered and went

to bed, but not to sleep – The Birl purred the whole night, loud, joyous with

lion-sized volume.

The following morning Jenny accepted

our night-time stowaway with good grace, fait

accompli, and took us round to meet her orphans. We were charmed by the trembling baby

fruitbats, Flying Foxes, that we all helped dropper feed. Adults fruit bats, huge creatures whose wings

can span a metre or more, are very gentle, and feed on fruit and nectar. The orphans are a nightly collection as

parents suffer electrocution on the huge overhead wires. Flying Foxes do not have the fine radar of

their tiny cousins, relying on sight, which fails them on flight. They also succumb to a deadly tic paralysis.

Our itinerary for the day included

lunch with Rose, a German artist, who was horrified when we turned up with a

feline on her property! She refused to let us take The Birl out of

the car, fed us rapidly, and equally rapidly gave us the phone number of a

group of apartments in Port Douglas, a magical place on the sea’s edge between

reef and rainforest, and to where we would now head instead of Cairns and the

Tjabuki story. I phoned and established

a wonderful rate for locals, Townsville being considered almost local, and the

rate was even more attractive since the collapse of Ansett Airlines a couple of

weeks earlier which had ruined the tourist economy. I then confessed about the

kitten. The answer changed to a

regretful no. So I asked the woman I was

speaking to if she could give me six other phone numbers of apartments in Port

Douglas as I had to find somewhere to actually come to that night. She went to ask her husband. He came to the phone. He was English and the smile in my mind’s eye

returned. I said I was so sorry he couldn’t take us and our

kitten as his apartments had been recommended to us, but could he please help us with other local phone

numbers as we were some way away and did not have their local phone

directory? He paused, there was a

longish silence, then he said, oh, you

can come here.

We knew then that the rescuing of The

Birl was definitely part of Caroline’s black Australia. The manager of the apartments was English,

and his wife was from New Zealand. They

didn’t mind cats in the slightest, and because of Ansett’s collapse most of

their apartments were empty so they gave us a superb cottage all to ourselves,

with its own garden, quite separate from any of the other accommodations, all

of which were attached to each other. Instead of being the usual $300 or more a

night it was only $80. In fact the whole

resort was almost empty. It was utterly

purr-fect and we all settled in for a marvellous week, knowing we could leave

The Birl in the safety of a deliciously cool and air-conditioned private

cottage while we went where we had to go.

The

Birl had taken to the travelling life as to the manner born. We could now leave her/him with food, water,

milk, biscuits and kitty litter while we made ourselves some ginger tea – real

root ginger, an amount of, peeled and chopped, steeped in boiling water – and

took off to explore the wonders of Port Douglas leaving The Birl to sleep,

still purring loudly.

St

Mary’s by the Sea, with its huge picture window behind the altar, framing a

view of the sea as pristine as on the day of Creation, the little white timber

building ringed by foxtail palms, the prettiest of all palms, which stood like

prayers around it, enchanted us. Along the bay the shops were magnets for two

middle-aged women seduced by must-haves for a walkabout ... but first,

food. Immigrant Italians had long since

left the cane fields and were now creating gastronomic history with restaurants

of quality and menus of imagination: penne and gorgonzola, spinach and cream

sauce served with rocket salad brought forth paeans of praise and in turn, very

full tums. We waddled home to fall into

our respective beds and sleep the sleep of the just. The Birl chose Caroline to sing to, all

night.

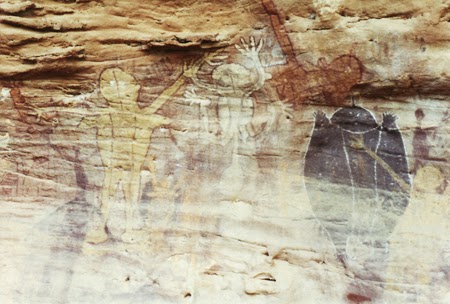

I was prompted to visit Split Rock on

Friday. Split Rock is a marvellous gallery of Aboriginal rock art as old as any

similar rock art to be found in France, and Friday sounded in my mind’s ear

loud and clear. We spent the interim

days exploring the stunning Mossman Gorge and rainforests, and the rather lush

shops in the small, elegant main street of Port Douglas. No sign of any Aboriginal elder for Caroline

to meet there, but we were both finely tuned to timing – and to being awake to

the Hint. Friday, we knew, was part of

that Hint.

One morning I woke early and went for a

walk. I walked in a meditative state,

inviting the world of Spirit to help. On

my return I passed a car rental office just three doors from our

apartment. It was six o’clock in the

morning. A man was washing a very new

off road vehicle. I stopped and asked if

we could hire one from him, and would he mind if we took it to Laura, on the

way to the Gulf Country? The road was a

devil of a dust bowl, and dust does dreadful damage to every nut, bolt, vent

and seat cover of every car to ever travel it.

He agreed to the journey, with precautions, and thus we had a very grand

car for our proposed adventure. I walked in to our apartment to find Caroline

giving The Birl its second breakfast and told her of our new car.

This morning we were going to relax and

play ornithologists at the Daintree Rainforest Environment Centre, under the

spell of the Curator who was passionate about his responsibility. Hours later we went ‘home’ for lunch, topped

up The Birl with food, milk and water, and with a certain impetus took off for

Mossman Gorge.

The rainforest is spectacular, cool

mossy gorges and escarpments lined with massive trees, epiphytes and vines;

colossal boulders like Narguns ensconced in and along the chilly streams,

creating shallow pools of beckoning refreshment from the steamy humidity. Electric blue Ulysses butterflies darted

around us, some as huge as my hand. We

had entered another world. Disdaining

the loud presence of other bathers we walked on as far as a wood and chain

suspension bridge, and saw a perfect pool beneath it. This was meant for us. Clambering down the rocks we pulled on our

togs, rolled up our dresses to place on a rock and laid down our wickedly

wondrous hats. The water made us gasp

every body-inch of our slow descent.

Then Caroline could bear it no more and sank in to her neck. That gasp reverberated over the rocks! I followed with inching gasps. The water was sublime, its chilling effect exhilarating.

We felt cleansed throughout; it was a

subtle baptism for the journey to Split Rock the following day. With hours of daylight still left and

vivified by the water we considered going on to Daintree River afterwards. Unsure of how far it was I pulled in to the

Kuku Yalandji office for guided walks at the entrance to the Gorge. We parked the car and walked up to the door.

The office was a smallish room with a

few pieces of indigenous art, some posters, and a glass counter behind which

stood one of the most beautiful young women I have ever seen. She was so beautiful in fact that I did a

double take as I walked through the doorway.

She was busy fiddling with the till, a computerised piece with a mind of

its own apparently. Exasperated sounds were forthcoming at closely spaced

intervals. In the opposite corner a

small slim Aboriginal man wearing a baseball cap was showing a couple of

tourists a didjeridoo. We wandered

around for a minute or two until the young woman asked if she could help us. We asked her vaguely about something,

everything turned vague, I had forgotten about Cape Tribulation or Daintree or

anything else. Caroline appeared just as

vague for some reason, though she focussed on buying a booklet about the Kuku

Yalandji. The tourists went out, the

Aboriginal man left too.

Then another Aboriginal man walked

in. He was, as Caroline said afterwards,

a most beautiful man. Small, slightly

built, wearing an Akubra style hat over thick grey hair, grey bearded, very

softly spoken, an aura of arcane calm surrounding him. The beautiful young

Aboriginal woman behind the counter referred our vague questions to him. We turned, to give him our full

attention. We said we were going to

Split Rock on the morrow and I asked if there was anything we could do, or

could take as a gift to Spirit that would guide us into walking there in a

sacred manner? When I walked a little of

the shaman way down in Grass Valley and Santa Fé many years earlier with the Inuit

from north of Nome, I was instructed to leave tobacco for Great Spirit, for

tobacco is one of the great healing herbs.

Our abuse of it betrays our ignorance.

The man looked quietly at us, introduced himself as CJ, and gave us his

Aboriginal name too. He said we did not

need to take anything, but stepping back lightly he swiftly placed each hand in

turn under his armpits and just as swiftly withdrew them to draw them down from

Caroline’s head to her toes, as if stroking her aura. He repeated the process with me. Now, he said, Spirit will welcome you, you

carry our scent. Caroline then told him

she had been waiting to come to Australia since she was ten years old, and she

was now sixty.

CJ said softly: that’s a long time to

wait to come home. He began to explain that he was not from that

country, Split Rock country, that was Quinkan country, but at that moment

Caroline gave a shocking cry, clasped her hands to her head and almost

collapsed on to the glass counter. CJ

was unperturbed, so was I apart from the obvious concern that my friend was in

quite overwhelming pain. Sonja, the

beautiful young woman, brought a chair.

Caroline sat heavily into it, by now she was sobbing and crying out with

the searing pain bounding from side to side of her head as she clutched

it. CJ placed his hands over it, but

said I cannot heal her, she is not in my country, and Sonja said she would call

Harold, the young man who had been showing the didjeridoos. He belonged to the country here.

Harold came in, his eyes flooded with

compassion when he saw Caroline’s state.

Briefly CJ repeated what had passed between them. Harold said he was a healer, a shaman in

training with his father, who was trained by his father to be a healer for his

people. He had not quite completed his

long apprenticeship, but if Caroline would give him permission he would offer

his healing power. He was so humble,

almost reticent, but his eyes were deep pools of compassion. Caroline could barely whimper: yes, please, I

understand about healing because I am a healer myself. Harold placed his hands on her head and I

witnessed an astonishing phenomenon. As

I watched Caroline’s face its familiar features underwent a dramatic change,

her nose widened, her mouth changed – I took an involuntary intake of

breath. There in front of my eyes was

the face of an old Aboriginal woman. It

was still Caroline, but it was as if a face from long long ago had been

revealed, had come home. All the years I

have known her I have always described Caroline to other friends as having

Aboriginal eyes. They are the colour of

honey, of amber, (which Aboriginal eyes aren’t necessarily); and I always

remember them as having no pupils, (which Aboriginal eyes don’t necessarily

lack). In fact Caroline’s eyes aren’t

really Aboriginal eyes at all – but they

were now as they looked out of an ancient face carved out of time. Caroline does have pupils, but at times her

eyes seem to reflect light from the inside, rather than from the outside. I have seen this phenomenon in an Afghan, a

Kurd, and an exquisite Indian girl, a beggar rag picker whose radiant smile lit

up the railway station at Jaipur.

Harold then stood in front of her, his

eyes focussed directly to her head, his hands held above. Long long minutes passed. At length Caroline relaxed and managed a weak

smile. Her face resumed its more

familiar aspects. Harold then asked if

he could look at her aura, he found it in good order, grey, red and blue, quite

a different sequence of colours to those popularly seen by western healers. He

acknowledged the difference before he told her what he was seeing. We all relaxed. In due time Harold left as quietly as he had

come. He said that he thought the pull

of Spirit back to Australia was too powerful for Caroline’s body to cope with,

which was why it was so painful.

Caroline and CJ continued to speak, and CJ said she should go to his

country for healing. He said again that

she had waited such a long time to come home that it seemed she should go to

his healing place, many hours from here.

He may be going there himself, and he may not, but up there terrible

things had happened. It was a place of terrible massacres 100 years ago – his

father was a tiny boy and saw his own father shot under him as he was running

with the small boy on his shoulders to escape the ‘bully men’ (whitefella) who

came out at weekends to slaughter Aborigines. He had a healing place up there

now, it was his country. He looked at

Caroline intently, but softly: and my country, he said, is named Woman’s

Dreaming. The words hung suspended in a

cocoon of magic and power. We both heard

them.

CJ turned to Sonja and asked that she

give us some leaflets about this place.

It was named Yindili. On the

simple leaflet were the words Healing Sanctuary, Welcome to Buru, Be Part of

the Dreamtime Healing. Caroline started

to clasp her head again, crying oh no, not more. CJ and I glanced at each other and said

simultaneously, you must go to Yindili, it will be a healing. I remember that

when I stood on Gallipoli, not through any national sentiment, I felt the

unquiet spirits of countless men and boys, ANZACS, Turks and Kurds, overwhelm

me and I wept when I read the words of Ataturk carved into the opposite hill:

Traveller

halt! The soil you tread

Once

witnessed the end of an era.

Listen! In this quiet mound

There

once beat the heart of a nation.

Grey Wolf, the Inuit shaman, told me

that in times of terror the earth prays, and those who are sensitive to Mother

Earth can feel it through our heart, and through the heartbeat, and through the

songlines that link us to every living being.

We are all linked by that same heartbeat, the heartbeat of Mother Earth.

Caroline was now weeping quietly. CJ

looked intently at her and said, fifty years is a long time for Spirit to wait

to ‘come home’.

My mind raced ahead. This was obviously going to be Caroline’s

vision quest so to speak, not mine. This was a direction that Caroline needed

to travel alone this time. I asked CJ

mundane questions like roads? Four-wheel drive vehicle? Bedding?

Food? And similar things so that

I might be able to offer practical help for Caroline to access the wilderness

leading to Wujul Wujul, his country.

After all, Caroline was quintessentially English and I still felt she

needed enlightening as to the differences between the country lanes of Cornwall

and the slithery unsigned tropical rainforest tracks of Far North

Queensland. I seem to recall he gave the

vaguest wave of his hand in reply.

We said our goodbyes to CJ, he told me

to take Caroline home and let her sleep.

As we left he touched my arm and told me to come to his healing place

“another time”. This was Caroline’s

time.

Caroline collapsed exhausted on to her

bed, The Birl bouncing all over her. I

left her to rest and went down to the town to look for something sweet to bring

her for when she awoke, it would replenish the energy that had been drained by

pain. Chance encounters, each revealing

another hint that Caroline should make the journey, kept me away for a couple

of hours. I returned with a chocolate

mousse from the Coffee Club. Caroline was awake, drained by the pain, but she

had rested. She floored me by quietly saying

she had looked into CJ’s pupil-less eyes.

I looked at her, recalled how I often saw her eyes, and here she was telling me

of her experience of a true Aborigine. Wonder

was present.

I made a grand salad, we ate it

quietly, and I think we just showered and called it a day, knowing that Laura

and Split Rock was one helluva drive, as they say, the following day.

It certainly was, and unbelievably

hot. We learned later that temperatures

had touched 34C in Townsville, 39C in southern Queensland and 43C Out

West. Laura was Out West. It was like driving in through the doors of

hell. Even with air-conditioning on the

coolest possible setting the radiant heat and dryness outside the vehicle

parched our throats. The first part of

the journey was very pleasant though, up over the ranges through Julatten to

Mount Molloy for tea and toast, yoghurt and bananas. The mountains looked so cool and green from

where we sat. Once back in the car,

however, the road led us to parchment country very quickly. Hundreds of kilometres from Port Douglas we

turned left off the last bitumen at Lakeland Downs to enter the dust bowls of

hell. Well, I have seen worse, going

west from Hughenden was pretty desolate.

At least, in answer to my most fervent prayers at dawn, the road was not

a stinking charnel house of dead, maimed or dying cattle, kangaroos, wallabies,

pademelons, possums, emus, smaller birds, and tiny rodents. Night drivers must

have been on holiday. Miraculously we

passed only two road kills the whole day – a dingo and a wallaby. Both too obviously dead for us to stop and

check.

On and on and on we drove, the

occasional passing or oncoming car enveloping us in blinding dust storms. Straying cattle caused us to slow right down

to allow their unpredictable nature time to decide whether the brown grass

might be a greener shade of burnt on the other side of the road. Every now and then eagles soared on thermals

above us, or swooped low to catch an unsuspecting snake and wheel upwards with

it. The country was vast, dry, and every

shade of brown from palest fawn to deepest umber. Patches of blood red flowering abel moschus, a ground hugging plant

with flowers like hibiscus, caught our eyes from time to time. We drove on and on, eventually the distant

escarpments began to close in around us and we passed the campsite of the

famous Laura Festival. Shortly

afterwards the road became bitumen up until we reached the rock art

galleries. The short stretch of bitumen

was built to protect the ancient sacred painting from the contemporary

corrosion that traffic made of swirling dust, and while the art itself may have

been re-touched over its 30,000-year existence, preservation in these times has

become crucial.

Thankfully we parked, under a shadeless

tree. The few trees in the car park were

tall, with slender scorched limbs, twig-like, reaching upwards, sickle-drop

leaves in diminishing clusters cast no separation between white-hot sun and

searing light. We opened the car doors

and broke into a sweat. Jamming our hats

on our heads and filling our bilums with water bottles and some fruit we began

the long ascent to the galleries.

As we climbed Caroline’s face grew

pinker and pinker under her recent Spanish tan.

Concerned, we stopped, drank from our water, and continued in this

manner all the way to the colossal boulders that make up the first

gallery. The split in the rock for which

the galleries are named showed startlingly apparent as we rounded the last

mammoth boulder and reached the lee.

As we climbed Caroline’s face grew

pinker and pinker under her recent Spanish tan.

Concerned, we stopped, drank from our water, and continued in this

manner all the way to the colossal boulders that make up the first

gallery. The split in the rock for which

the galleries are named showed startlingly apparent as we rounded the last

mammoth boulder and reached the lee.

Gratefully we sat on the wooden seats

thoughtfully provided by some funding agency or other, and silently drank more

water, relishing the shadows and the breeze caused by the height and the

funnelling of the air under the rocky overhang.

We remained in silence punctuated by the odd comment about the paintings

as their identity clarified: yellow women with grand breasts drawn at right

angles to their bodies, echidnas belly revealed, red dingoes, two men carrying

a lung fish, huge turtles, short mischievous Quinkans and very tall good

Quinkans. Handprints spray-outlined with different ochres could be faintly

seen, and the folds and crevices of the boulders themselves lent more than

mysterious faces with lopsided grins and winking devilry to the scenes in front

of us.

Modestly refreshed, though the

word says far more than it should in describing two dripping dames, we gathered

up all our remaining energy and staggered up to the next two galleries to peer

at full length good Quinkans and other animal drawings. There were no seats there and we staggered

back down with decisively mutual swiftness.

There are many more galleries up on the higher escarpments but the

suffocating heat already had us staggering.

After an hour or more of just being there I stood up and walked to a

large stone bowl under the main overhang.

It was filled with sand and ash, so it was obviously used. I lit incense and turned to face East. I prayed for many things, for Caroline’s

sacred journey, for Afghanistan, for the refugees Australians were so churlish

about allowing in (in this country everyone has come from somewhere else, some with

far less claim to sanctuary or asylum than the poor wretches currently out at

sea). For many things I prayed, and

included one for me, that my books may find a publisher and my own destiny unfold.

We had, Caroline and I, both chosen

with care our dress for this special day.

There really was only one option – our almost matching Java Bazaar loose flowing numbers with

deep ochre Wandjina type Aboriginal figures on the black or navy

background. Caroline’s was black and

mine, one of a number of virtually identical dresses bought over the years for

their coolness, their acceptable price, and their elegance, was navy. We had no hesitation about wearing such

similar clothing, and with our splendid hats we knew we cut a dash. Not that those considerations were the

purpose of a pilgrimage. Our purpose was

to honour the tradition we were entering, and to blend, as much as it was

possible for two whitefella middle aged matrons, with the environment.

Breakfast in Mount Molloy had caused much favourable comment about our mode,

and another photo or two. We now quietly

stood and whispered ‘yalana’, thank you, to the ancestors for granting us this

blessed time.

We could hear voices and

knew a tour group was about to appear.

As we rounded the first boulder we were met by a breathless group headed

by a woman of our own age wearing stiff white shorts, a tucked in shirt, socks

and trainers. Her face was the colour of

raspberries and she was awash with sweat. Her jaw dropped when she beheld us,

now cool and elegant in sandals, flowing appropriateness and Ascot hats. She held us in inconsequential conversation,

eyeing us all the while. I laughed. She then said how marvellous we looked, and

we agreed! I knew that her clothes would

not allow her to cool down, but instead would hold the heat. I said, grinning, we women don’t need to

cross-dress, leave that sort of gear to the men! At that moment their guide appeared, dripping

with sweat from his regulation trousers, long sleeved shirt, belt, socks,

boots, and stifling felt Akubra. “Youse

look cool,” he said in good vernacular as we sashayed past…

No clothing really combats such

temperatures, but it is likely, in my modest view, that Arabs know a darn sight

more about cool dressing in the desert than the Aussies who simply carry on the

myth of mad dogs and Englishmen…

Looking up at the vast and ancient

rocks we said our final ’yalana’ to the Spirits who allowed us such time alone,

and drove on into Laura to fill up with petrol and buy more water for the long

drive back. It was dark when we arrived

– the total journey was nearly 600 kilometres.

Caroline was wising up about distances in the Big Country.

We showered, filled up The Birl with

food and milk and water and lots of cuddles and then dragged ourselves downtown

for a slow purchase of an opera length rope of baroque pearls from Wicked

Willie’s that Caroline knew she couldn’t live without, and a quick supper that

I knew I couldn’t live without.

That night I had an astonishing dream.

It wasn’t actually a dream because the shock of it awoke me and I could see the

same vision with wide-awake eyes. A long

Quinkan-thin ancient Aboriginal man was hovering above me. It was as if he was

searching my soul.

When Caroline woke I told her of the

experience. She had not dreamed but she

told me that yesterday from the time of leaving the bitumen at Lakelands she

had seen, bounding alongside the vehicle, unnaturally tall and thin Aboriginal

men, carrying spears and keeping up with us all the way to the car park at

Split Rock. She said they then left us,

and were not with us for our return journey.

We were left wondering. Were they

ancestral spirits of humans, or Quinkans?

We tacitly agreed today would be a day

of sloth and recovery. We had both been

affected by yesterday’s excessive heat, so today’s agenda was to do as little

as possible. And I do confess, writing

this, that that day remains a complete

blank for me.

Sunday was decision time for

Caroline. The hired car from Townsville

needed to be returned by Tuesday, which meant leaving on Monday at the

latest. If she was to get to Wujul Wujul

Caroline would need to again hire an off road vehicle and contact the ‘old

fella’ to let him know she was coming.

After breakfast she phoned the number CJ had given her. CJ was not there, but she explained her story

to the voice on the phone who said, in turn, he was leaving that place and

would be in Mossman that evening. He

introduced himself as Sunny and asked if we would like to meet him there? A place and time was set and Caroline

replaced the phone. Suddenly she gasped,

and clamped her hands to her head, crying oh no, not again!

Speaking to this man had precipitated a

recurrence of the shocking pain in her head.

She went to lay down and I spent the next hour wetting and freezing tea

towels and applying them to her head.

Eventually she said, I have to go, I simply have to go, tomorrow, and

having said it, her headache ceased.

Later she went to book the four-wheel drive, and we spent the day

packing our belongings and planning for all contingencies. I would take everything back with me to leave

Caroline with one tiny bag for toiletries, a change of clothes, torch, her

journal. Buses left Port Douglas for

Cairns regularly and she could get a coach to Townsville from there, it would

take around six hours. She phoned Darren,

she had re-named him Darwin, to tell him I was returning the following day with

Black Australia. O no, he said, without a frisson

of discouragement, not another cat…

We met Sunny as arranged. Much of the conversation was desultory, quasi

political, speaking again of the terrible massacres that had taken place,

filling in details that history will never own.

Details like the ‘bully men’ who slaughtered half-caste children because

white men denied any liaison (a euphemism for rape) with Aboriginal girls and

women. After some hours skirting around

the real issue that was burning Caroline so much Sunny said that if Caroline

was to make the journey north she should go back to the office of Kuku Yalandji

and ask CJ’s sister to arrange for someone to accompany her. He made a couple of lengthy phone calls to

someone, and gave us a dire warning that The Wet was imminent and Wujul Wujul

would then be inaccessible. He then said

something that turned me into an amalgam of goosebumps. That country, he said,

that country is Woman’s Dreaming. Only a

woman can heal that place. Caroline heard

it too.

That night we had eleven inches of

rain. Looking out of our windows the

following morning we saw the roads had turned to rivers. Unperturbed, Caroline planned. We said our goodbyes to each other. I knew nothing would stop Caroline now, and

equally, in spite of every possible obstacle placed before her, I also knew she

would get right to CJ’s father, and in their meeting would be the healing.

As I drove south the rain was so

blinding I could only crawl, even with full beam headlights all I could see was

a wall of water. No traffic passed me,

neither did I see any coming in the opposite direction. Anyone else was being as cautious as I. The Birl was curled up in the big round

Burkina Faso basket that I had placed on the passenger seat, as calm and

trusting as could be. The rain eased as I entered Cairns, but not before I had

taken a wrong turn which made me miss the by-pass road. Out of the city the wall of rain descended

again, deluge after deluge. I prayed I

could get through Tully and Ingham, notorious for flooding and cutting the

townships off for days, preventing onward travel to Townsville, which was

home. Rainfall in the Wet Tropics is

fabulous in every sense.

Miraculously the rain clouds veered

west over El Arish which meant I had a dry run through Tully, and for all the

hundreds of kilometres left on the home trip.

I made one stop, to visit friends on Crystal Creek where I knew I would

be given a warm welcome and a huge armful of roses to take home. Every time doctors shake their head over the

state of Fred’s heart he just orders another 200 roses to plant and bud and

graft and lives on regardless. Go and

enjoy your roses, is now the catch-cry for longevity. Fred was sleeping when I arrived, and Merle,

herself a true old-fashioned rose, took me round their gardens, cutting this

bloom and that as she went.

Days passed. I heard nothing from Caroline. Then she

phoned, the Wet had threatened them all and CJ’s father had told her to leave

for her own safety. She had made it back

to Port Douglas and would be home the following afternoon. Meanwhile The Birl proved to be a boy and to

complement Darren’s Arthurian contingency of felines he was duly named

Merlin. Arthur loves him, Nimué is

keeping her distance - and Merlin’s just happy being Merlin.

Caroline’s

Story

After collecting Caroline from

Townsville Transit Centre we came home and sat on the large verandah as I

listened to Caroline’s story. After we

parted she drove on to the Kuku Yalandji office to find it closed. She went round the back to where she could

hear voices and introduced herself. The

woman smiled a welcome, said she was CJ’s sister and told her to make a cup of

tea for everyone. Gail heard Caroline’s

story, but no, there was no one to go with her or guide her through the

rainforest. However a mudmap was quickly

scribbled, the directions were, essentially, cross the Daintree on the ferry

and keep driving north until the Black Stump (a proverbial bush icon) and turn

left. Keep driving. That was it.

Easy, thought Caroline.

She set off. The rain was a blinding wall, driving through

it was to challenge all her expertise.

Some time passed and Caroline reached the Daintree ferry. She was the first on. She sat in the car thankful for the

protection it afforded against the deluge outside. Musing on the many moments that had led to

this moment she was dimly aware of an agitated male voice calling over the loud

speaker system for passengers to come and get their tickets, the ferry was

shortly due to depart. More and more

insistent came the voice. Suddenly a

good British penny dropped: Good heavens, registered Caroline, he means me!

He wants me to climb out of

this car, drown in the deluge to reach him

in his dry little space, and buy a ticket!

She battled with this upside down process for a minute, realised she was

downunder anyway, and with a certain aplomb, battled her way through a wall of

rain to purchase a ticket from a smugly dry man. A certain lack of gallantry registered,

particularly as she had travelled on many such ferries in her time around this

planet and not once had any ferryman ever expected drivers to step down from

their cars to come to them!

Across the other side she had far more

pressing concerns. The rain continued

like a blinding silver sheet to diffuse her visibility to a matter of feet

ahead of her. Dimly she was aware of

slithering escarpments either side from time to time and of waterfalls bouncing

across the road threatened to careen the car over the track at every turn. Hours past.

From time to time the rain eased and Caroline was able to thrill to the

sheer beauty of the glistening forest around her. Then the bitumen road ran out. She was on mud. And slippery mud at that. The rain increased, driving on the track took

every ounce of concentration, waterfalls were now flooding the road, which was

still ascending, trees were blown down, huge vines weighed down by water draped

across the track. Eventually she saw the

equivalent of the proverbial black stump, and turned left. The road didn’t look much like a road, just a

river of slithering red mud spewing onto the Wujul track. Water gushed down it, and creeks either side

of it were rising in front of her eyes, threatening to engulf any suggestion of

passable track.

On and on she struggled to keep the car

to the tracks which she was not even sure were under her. As she told me the story I did not think I

knew of many people who would attempt such a perilous undertaking alone, without

telling rangers and without a mobile phone.

Innocence commands the protection of angels. She drove on this terrible terrain for nearly

an hour. She held the slithering vehicle

as straight as she could, and saw all around her the creeks rising and fallen

trees building up to roadblocks. Through

a second gate she went, and finally admitted she could go no further. There was no indication she was even on the

right road, though she knew the directions of drive north towards Cape York and

turn left were about as accurate as she could expect – there was, after all,

only one road from which to turn.

Gathering all her strength Caroline

managed to turn her vehicle around without canyoning into outer space on either

side of the track and reluctantly set to return the way she had come. She prayed, and prayed. If I am meant to do this, she prayed, I need

help, I need a guide.

A long half-hour further on and the

rain eased again. She knew she was

nearly at the original turnoff.

Suddenly, to her left, she saw an Aboriginal sitting in a clearing with

his swag and esky. Stopping, she called

out to him and asked him where was PJ’s place?

You just come from his place, he said, bit further on. Oh please, she pleaded, can you come back

with me? Well it just so happened he was

waiting for his mates to come down from near that place to pick him up. He had driven his girlfriend’s car down this

far as she was too frightened to drive alone, she had gone on and he was

waiting to go back up. If she didn’t

mind his muddy boots then he’d come with her.

They would pass his mates on the track.

Which they did, the sight of which made Caroline chuckle. Driving an open top Jeep both men wore

swimming goggles against the sheeting rain, and one had a woolly snood tucking

all his hair back. The Red Baron’s

brother was alive and well.

The men took it in turns to get out and

drag fallen trees from the track, open and close gates, warn her when they were

approaching the treacherous red mud which drew the car down into its sticky

substrata and threatened its progress.

As they climbed higher the rain eased again, and quite suddenly the men

halted, told Caroline the place she was looking for was over the next ridge,

and said goodbye. She cruised into China

Camp and pulled up next to a man painting a corrugated iron construction sky

blue. It was CJ’s father’s new shower

room, and he wanted to bring the sky in.

She was given a bed, and her pillow had clean T-shirts over

it as a cover. All had been prepared as

the men sensed someone was coming, they sensed it was a woman, but in such

intimidating weather they did not for a moment think that the English lady

Sunny phoned them about would make it. How she went, alone, in a hired

four-wheel drive, in the most ghastly weather conditions, is a remarkable

story. Once we had made the connection with CJ he did not accompany her or

guide her, he only told her to go to his country to meet his 84 year old

father, Chala. That first night a grand

stew of vegetables, chilli and fish was prepared, washed down with copious

amounts of black smokey ‘billy’ tea, and followed by doorstops of white bread

and thick butter.

CJ’s father told Caroline a story from

his younger days of when he used to cut sugar cane all the way from Daintree

down to Ingham. On one of those days he

was so exhausted that he collapsed and died.

He was declared dead, but during his ‘death’ Jesus came to him and told

Chala his time wasn’t up yet, he had to go back. But before he ‘left’ to return to his body

Jesus asked the Angels to show Chala a Spirit place, and the beauty of that

place was beyond compare. Chala did not

want to return to earth, but such was the force that he sprung back to “into

his body” (and the man holding him had a coronary – but that’s another story)

and lived on. For the last few years he

has wanted to go back to the Paradise he had glimpsed, but he knew it was still

not his time. Caroline gave him her olive-wood

carving of Our Lady that she had bought from World Vision. Chala’s eyes filled with tears. He told her that many people came to this

place and they cried. It was now his

turn to cry. This was a healing. A woman had come all the way from the Queen, his

way of saying whitefella’s country, to be with him and understand his story, to

walk on a land of painful memories, a land known as Woman’s Dreaming. Faith and love, answering a call of half a

century and how many lifetimes, had brought healing full circle.

Yundu

Ngulkurr Baja Ku – Yundu nguli jawan ngulkurr bajaku

Yundu binil bajaku

Yundu kuku manu baja

Ngali wawu jiday jundu!

Wawu Baja, Jinkalmu.

We

love you very much for coming to see us.

Jinkalmu,

wrote these farewell words in Caroline’s journal, thanking her Aboriginal guide

for bringing her to them. She

cried. Chala cried. Jinkalmu cried.

Afterword – Twelve Years Later

Some months after Caroline had returned

to England I too left Australia, having lived there more decades than I care to

recall, to settle in Glastonbury. I was,

and am, passionate about Australia, the country, the wildlife, its beauty. Yet it was when I returned to the landscape

of my birth (and even more so, France, the landscape of my ancestors) that I

discovered the land speaks to us. Its voice is the language the ancients knew,

soil resonates with soul. The soil, Jung

wrote, is in the soul; soul is in the soil.

Aborigines know this, Bushmen know this, Native Americans know this, the

desert Arabs know this, Bedouin know this and, actually, the English know this

too. Not all of them it’s true, but with

their passion for nature and animals and gardens this ancient knowledge is

subliminally recognised. Ancient

churchyard yews speak when we listen; ancient stones sing when we open

ourselves to hear, the older pagan ways are clear to us; in the West Country we

wassail and sing to the apple orchards; put milk out for the hedgehogs; walk

the old straight track ways; marvel at sheela-na-gigs as church corbels more

than a thousand years old, affectionately refer to cracks in the plaster of our

old homes as leylines.

Nature is fecund here, fecundity is

feminine. The womb of life is landscape,

replete with legend and myth and a sure sense of its ancient sacred access ways

to the Great Goddess who gives life to all.

In

May 2013 Caroline and I spent two blessed weeks together on Gozo. It was the

first time since our Walkabout that we had such a gift of time to ourselves.

After some days busying ourselves with social commitments and sightseeing our

conversations drifted to reminiscences and the deep connections Caroline had

made with Chala and Jinkalmu. They had kept in touch for a while, though were no

longer. Caroline shared their letters with me and when I returned home I

re-read her Walkabout story and was brought up short by our mutual experience

of eyes.

At

once I sent her an email:

|

From:

|

Zoé d'Ay

(phaedra@hotmail.co.uk)

|

|

Sent:

|

16 June 2013 06:10:21

|

|

To:

|

CarolineVasey (carolinevasey@hotmail.com)

|

Caroline dearest

I have re-read your Walkabout story. On page 13 I nearly fell off my perch. You wrote of our first meeting with CJ: He looked at me with deep brown velvet eyes, pupil-less eyes ... did you really mean pupil-less? Did CJ really have pupil-less eyes?

If so then I suspect that

is why I always saw yours like that (even though it's perfectly obvious your

eyes are normal). I was seeing your spiritual lineage of healers. Mrs Tweedie

said that we always have a recognizable face, incarnation after

incarnation. She said, firmly, we have never been grasshoppers and

neither do we alternate sexes; what we do, regardless of popular assumptions,

is remain our singular sex until we have developed perfectly the balance within

us of opposite qualities. Then we can function as a whole - holy - human

being. Makes perfect sense to me, especially when she pointed out with

photos I had given her that when the bodies of many holy men, including Father

Bede, reach an earthly perfection of male/female qualities their body will assume

'breasts' and lose its bodily hair.

Women who have reached

that level of unity, which Jung named the hieros

gamos, develop a stronger voice (enlightment for women comes through

the awakening of Vishuddhi chakra, the throat, re-awakening our lost voices)

and are noted for their facility for clarity and a singular focus. Hieros gamos is the inner marriage, the

Sacred Marriage and is always symbolic (two butterflies; Father Bede and

the Black Madonna; Godwin and his Divine Feminine). It is the

harmonization of opposites within.

Summed up: Hieros gamos - Greek ἱερὸς γάμος, ἱερογαμία, meaning "holy marriage" - refers to a

ritual that plays out a marriage between a god and a goddess. In some

societies human participants represent the deities. Think Arthur and

Morgana le Feé; Egyptian pharaohs, brother and sister. Hieros gamos is used in its symbolic of

alchemical context as Jung, the wise old man of the West, understood.

Why am I saying

this? Because of the pupil-less eyes. Symbolically the Mimis and

all the other rock art of Aboriginal Spirit Beings have no pupils to their eyes;

and those very spiritual men we met on our pilgrimage were all soft-bodied,

feminine without the trace of effeminacy. Well, well, well!

You would have seen the

pupil-less eyes of CJ, you would have seen them with your spirit eyes. In the context of CJ, at that moment I

wouldn't, it not being my lineage, even though I clearly saw it in you.

Aren’t we are blessed to

know these things, and to know each other,

Love you!

Caroline replied, Yes, she had indeed seen

CJ’s eyes on their first encounter exactly as she described. These are

mysteries; we are blessed to know them.

In August 2013 I re-traced my own steps,

returning to FNQ after twelve years absence. A friend surprised me by driving

me north from Cairns on a memory lane moment. I visited Karnak to say my

goodbyes to Diane Cilento; she had been my guest in Glastonbury, we shared

mutual spiritual affinities, cats. On

that day a very unfriendly vigilant chased me away, but not until I had said my

farewells to Diane’s memory. The coffee

lounge in Mossman where Caroline and I met Sunny was unchanged, I sat in the

same seat I had sat in before, by the huge picture window, an amalgam of

goosebumps. An old Aborigine walked past the window and the whole Walkabout of

2001 passed in front of me as a vision, paralysing speech as an upwelling of

tears flooded my eyes, bathed my face. I had come full circle, given credence

to my own pilgrimage.

The landscape of the far Tropics is a woman’s

landscape – fertile, soft, majestic, lush and the humid air lies like silk on

the forearm – a part of me flies there in dreams.

Zoé d’Ay

2001 - 2013